Iain Merrick discovered the IF community back when Curses was the hot new game, rec.arts.int-fiction was a hotbed of discussion and the IF Archive was on ftp.gmd.de, and he’s been hanging around ever since. He wrote an HTML-TADS interpreter called HyperTADS and a Glulx interpreter called Git, which seemed like a good name at the time. And no, he hasn’t finished writing Tourist Trap yet. Right now he’s working with Steve Jackson and inkle studios to bring their Sorcery! gamebook series to Android.

The finalists for Best Technological Development were Twine 1.4, Versu and adv3lite.

What are we looking for in this category? For me, there are two main criteria:

- It should be something that does the heavy lifting for IF authors, making some cool new technology accessible to ordinary mortals. Last year’s winner Vorple is a terrific example: adding multimedia to an Inform game was previously very hard, but Vorple makes it vastly easier.

- Harder to quantify but I think equally important: it should be generative, enabling multiple unexpected new applications rather than just one cool new thing. A good example might be Inform 7’s extension system. All good IF languages are hackable and extendable, but I7 was the first to streamline the process of creating and publishing extensions. As a result, I7 authors now have hundreds of well-organised extensions to choose from, and can easily mix and match them to create exactly the kind of IF experience they have in mind.

I’ll review the 2013 finalists with these criteria in mind.

Twine 1.4

First up is the latest version of Twine, a system for building choice-based games and publishing them on the web. This is the least “new” of the finalists in that it’s an incremental update to an existing tool; there are ambitious plans for Twine 2.0 but that’s still in development. Does 1.4 have enough going for it to justify a XYZZY award?

First, an admission: I’ve never used Twine before! So I thought I’d better follow the same approach I used last year, and try my hand at writing a Twine game from scratch. What kind of game? What else but Cloak of Darkness!—Roger Firth’s wonderful little template for IF language comparisons. Admittedly this is slanted towards parser IF, but that’s what I’m familiar with, and I was interested to see how well (or badly) it translated to hypertext.

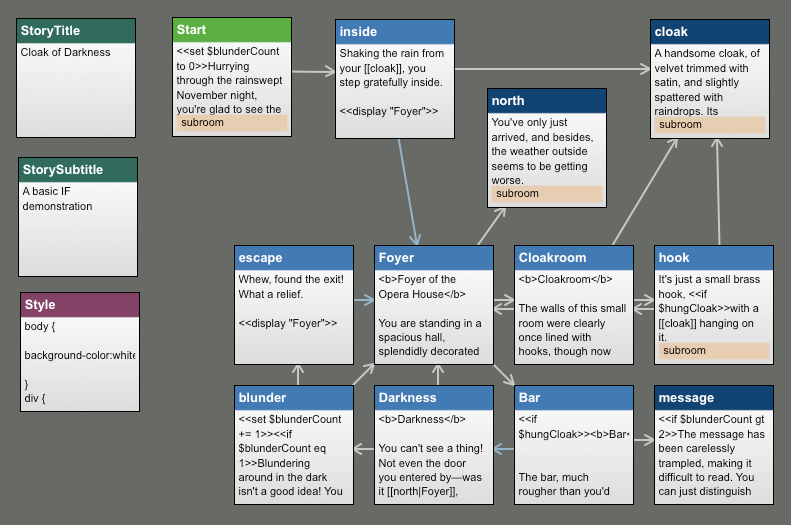

I downloaded Twine 1.4.1 for OS X, and the quick summary is: it works, and it’s really easy to use! I can definitely see why so many authors love this system. If you just want to write and add some simple hypertext touches, it’s better than anything else I’ve seen. If you have some more complicated logic in mind, Twine will support you—to an extent. I wasn’t able to get Cloak of Darkness working exactly the way I wanted, but I got most of the way there in just a couple of hours, starting from scratch with zero prior experience. Here’s what I came up with:

I’ve uploaded it to philome.la if you’d like to give it a try.

Here are a few things I particularly liked:

- Links between passages (Twine’s central unit of organisation; think of them as pages, paragraphs, rooms) are automatically checked. If you link to a passage that doesn’t exist yet, the link is highlighted in red and there’s a menu option to create the appropriate passage. This makes it easy to quickly block out your game’s structure—although a keyboard shortcut would make it even easier!

- There’s simple but effective syntax colouring for both Twine code (generally involving

<< >>and[[ ]]) and CSS stylesheets. - Passages can have tags, which you can use to associate them with stylesheets, making it easy to have several different passage types without having to style them all individually.

- It’s very easy to include pictures in the game.

Many of these features are new in 1.4, nicely answering my question of whether it’s a worthy update.

Things I didn’t like so much:

- The built-in text editor is usable but a bit underpowered. When copying-and-pasting Cloak of Darkness room descriptions, I missed features like comment/uncomment, indent/outdent, and add/remove line wrap.

- More generally, Twine’s newline handling seems needlessly fiddly: all newlines are copied directly to the output text, with a

<<nobr>>command to remove all newlines from specific sections. (From the release notes it looks like this feature has been tweaked several times, which I think supports my point: the command used to be called<<silently>>, and Twine 1.4 also allows you to use backslashes, which feels very hacky.) It would be much better to follow the lead of Markdown—translate two or more newlines into paragraph breaks, and strip out single newlines completely. That would make it really easy to mix code and text without messing up your formatting. - It’s hard to combine hypertext (where each link takes you to a completely new page) with “stretchtext” (where clicking a link just modifies or extends the current page, a la Undum). For Cloak of Darkness I originally wanted each room to be a separate page, while examining objects within a room would just add more text to the room description, but I couldn’t figure out how to do this. You can get either one of the two approaches by picking the appropriate story format (“Jonah” for stretchtext, “Sugarcane” for hypertext) but not both together.

- I could have solved my problem via Javascript, but that’s also hard! Not to mention error-prone. I found some online discussions with some useful-looking code snippets, but also scary reports of incompatibilities in various browsers. It’s great that you can use Javascript if you want to, but this is where Twine ceases to do all the heavy lifting for you. (The online community is great, though, so you can probably find somebody to help you out.)

So how does Twine fit my two criteria? For heavy lifting, a resounding YES, if you can do what you want in core Twine and don’t need any Javascript hackery. Is it generative? Given the impressively varied games people have written in Twine, I’d have to say yes again. But I think breaking down that barrier between hypertext and stretchtext would be a huge improvement, and would enable even more crazy experimentation.

Another thing I’d love to see in a future version of Twine is tools for managing variables. Similarly to the way it displays a graphical overview of your story’s passages, why not a display of all the variables and where they’re used? You can see a simple list of variables via the “Story Statistics” command, but there’s so much more that could be done in this area. For example, refactoring (rename a variable everywhere in the code) or automated testing (assert that some condition must hold in a given passage, and report any paths that break that condition).

Twine 2’s big ticket feature, though, is a web-based editor. This means you’ll be able to both play and write games in your browser, no app installation needed. Very cool indeed!

I was fairly skeptical when I started this review—how interesting can yet another CYOA system be, really? But I’m coming around. Twine is fast, it’s friendly and it’s fun.

adv3lite

Next up is Eric Eve’s new library for TADS 3, which completely replaces its parser and world model (leaving only the core T3 programming language). This project is similar in spirit to David Baggett’s excellent WorldClass library for TADS 2—almost exactly 20 years old today! But whereas WorldClass aimed to be more powerful and general than the default adv.t, a major goal of Adv3Lite is to simplify TADS 3 programming.

Adv3Lite therefore omits some unnecessary features that often get in the way (sitting and standing, walls and ceilings, light levels). It also boils down the ‘object soup’ of Adv3 to a smaller set of more flexible base classes. Rather than hunting the library reference for exactly the class you need, the idea is that you can just adjust one of the built-in hooks on the class you’re using already. If it works, that would certainly meet my “do the heavy lifting” criterion.

Adv3Lite also adds some new features, inspired by modern IF trends and developments in other languages such as Inform 7. For example, it includes I7-style scenes and regions, and builds on Eric’s terrific conversation libraries. Whether this is truly generative depends on how flexible and extensible these features are: can I only write Eric Eve-style conversations, or can I adjust it to fit my own vision? There’s a tension here with the first criterion, as trying to be too flexible is arguably what makes the original Adv3 too difficult for many authors to use.

This is a very ambitious project. Properly evaluating Adv3Lite will be a matter of months or years, as authors try using it and as Eric and his collaborators update it in response to feedback; I won’t be able to do it full justice here. So again, I’ll just try my hand at a little programming and tell you how it goes. But I won’t need to write Cloak of Darkness from scratch, because Eric has already done so! (In fact I cribbed off his Adv3Lite version when re-implementing it in Twine.)

Before trying Adv3Lite I had to get a basic TADS installation working. On OS X this means using the command line, as TADS Workbench only runs on Windows, but if you’re comfortable with the Terminal app it isn’t too bad. I found the TADS 3 Quick Start Guide, pasted the sample code into cod.t and wrote a cod.t3m build script as follows:

-D LANGUAGE=en_us

-D MESSAGESTYLE=neu

-Fy obj -Fo obj

-o cod.t3

-lib system

-lib adv3/adv3

-source cod

A quick t3make -f cod.t3m and I was away—almost: I first had to mkdir obj, as T3 didn’t create the output directory automatically. This is exactly the kind of thing that’s likely to put off potential OS X users. I assume the situation is much better for Windows users, though. Anyway: it’s a game, it runs!

I now downloaded Adv3Lite 1.1 and set about installing it. Amusingly, despite being ‘lite’ it’s almost twice as big as TADS itself! (7.2MB for Adv3Lite versus 3.9MB for FrobTADS 1.2.3—not remotely a big deal in this day and age, of course.) I was pleased to see that what you get in that big download is mostly documentation; just the list of manuals is already pretty long:

- Adv3Lite Quick Start Guide

- Adv3Lite Tutorial

- Learning TADS 3 with Adv3Lite

- Adv3Lite Library Manual

- TADS 3 System Manual

- Adv3Lite Library Reference Manual

- Introduction to HTML TADS

…plus a detailed Adv3Lite Library Change History.

This is great, but rather overwhelming. It could really use some organisation, perhaps even one of those cheesy flowcharts to tell you which book to start with (“have you done any programming?” “have you written IF before?” “have you used TADS?”) And surely there’s some overlap between these titles. Is the Tutorial really substantially different from a longer Quick Start, or a shorter Learning TADS 3?

I decided Quick Start was the best way to start quickly. Unfortunately I immediately hit some mistakes in the documentation. The sample code is called burglar but you’re told to compile it with t3make -f heidi (that being the game from the Tutorial, not Quick Start). And the sample code starts with:

#include <adv3.h>

#include <en_us.h>

This is simply wrong, as it includes the default Adv3 library, not Adv3Lite. I had to turn to the Tutorial to find the correct boilerplate:

#include <tads.h>

#include "advlite.h"

I then hit some further problems, but those turned out to be due to mixing up the Adv3 Quick Start with the TADS 3 Quick Start. I think that’s understandable, given the (real) mistake above, and that the two docs are otherwise very similar! I think this illustrates a potentially serious problem for Adv3Lite—it’s similar enough to Adv3 that you can easily get confused over which one you’re using (or which one a snippet of sample code uses), but different enough to give weird an incomprehensible error messages if you get the two mixed up.

After finally realising my Adv3 / Adv3Lite blunder, I decided to toss out all the sample code and give Eric’s Cloak of Darkness a try. To my relief, that worked straight out of the box. I was pleased to see how quick the compiler is—TADS 3 compiles each module separately, so only the files that change need to be recompiled. On a reasonably fast computer, you could easily have it compiling continuously in the background.

The game plays just as you’d expect. I decided I wasn’t happy with this response:

>hang cloak

I don’t understand that command.

>hang cloak on hook

(first taking off the velvet cloak)

You put the velvet cloak on the small brass hook.

Could I add a better disambiguation prompt for ‘hang’? More like its synonym ‘put’:

>put cloak

Where do you want to put it?

>hook

It’s just a small brass hook, screwed to the wall.

Hang on, that’s not a proper disambiguation either! Why did it interpret that second command as ‘examine hook’ rather than ‘hang cloak on hook’?

Here’s the code for the ‘hang’ verb (from Cloak of Darkness, not the library):

DefineTIAction(HangOn);

VerbRule(HangOn)

'hang' singleDobj ('on' | 'upon') singleIobj

: VerbProduction

action = HangOn

verbPhrase = 'hang/hanging (what) (on what)'

missingQ = 'what do you want to hang (on it);what do you want to hang it on'

iobjReply = onSingleNoun

;

modify Thing

dobjFor(HangOn) asDobjFor(PutOn)

iobjFor(HangOn) asIobjFor(PutOn)

;

Seems pretty straightforward. And the missingQ tells me there is in fact a disambiguation prompt; it’s just that the way you reach it is a bit weird:

>hang cloak on

What do you want to hang it on?

And that troublesome ‘on’ turns out to be the trick for ‘put’ as well:

>put cloak

Where do you want to put it?

>on the hook

(first taking off the velvet cloak)

You put the velvet cloak on the small brass hook.

I now see the logic behind the parsing, but I don’t believe anyone would ever actually type those commands. I decided to make the ‘on’ optional, but the documentation gave me no clue on how to do this; I had to hunt through the Adv3Lite source code to find the answer:

VerbRule(HangOn)

'hang' singleDobj ('on' | 'upon' | ) singleIobj

i.e., “on” or “upon” or nothing.

I decided I’d also like it to handle ‘hang up cloak’ and ‘hang cloak up’, but that gave even weirder results:

>hang up cloak

(hang us cloak)

You can’t put anything on the velvet cloak.

Curse you, autocorrect! That’s a cool feature, but not when it turns a partial command into a nonsensical one.

And that’s where I hit a roadblock. Again, the docs don’t explain how these features work, and I had to hunt through the library code. Handling of partial commands (“put on” without an indirect object) seems to be done as follows:

VerbRule(PutWhere)

[badness 500] ('put' | 'place') multiDobj

: VerbProduction

action = PutIn

verbPhrase = 'put/putting (what) (in what)'

missingQ = 'what do you want to put;where do you want to put it'

missingRole = IndirectObject

iobjReply = putPrepSingleNoun

answerMissing(cmd, np) {

/* ... lots of code ... */

}

priority = 25

;

And as far as I can figure out, autocorrect is buried inside parser.t, and can be enabled or disabled as follows:

autoSpell = true

But what I don’t want to disable it, just fix its interaction with my ‘hang on’ command? Something to do with badness or priority, maybe? I’m guessing it would take a lot of trial and error, and reading through the library code, to figure it out.

This makes me rather suspicious of how well Adv3Lite really fits my criteria. If I have to do a lot of careful reading and hacking to fix one verb, is the library really doing the heavy lifting for me? And if these two parser features interact so awkwardly, are there going to be other weird conflicts that get in the way of doing cool new stuff?

Admittedly I’m focusing here on the parser, which is just one aspect of Adv3Lite as a whole. What many authors will be interested in is the world model. One small nugget I like is the way you can define room exits really easily:

south = bar

west = cloakRoom

north = "You've only just arrived, and besides, the weather outside

seems to be getting worse. "

Now that feels like good old TADS 2! Much friendlier than all the TravelConnector business that TADS 3 introduced.

Without writing a complete game, I can’t tell whether that friendly feel lasts the distance. But if it does, that’s really promising—it would mean Adv3Lite turns TADS 3 into what many authors always wanted: a powerful and flexible programming language married to a simple, straightforward world model that does everything expected of a modern IF game. It wouldn’t be a huge leap forward, but it might be an appealing alternative for authors who don’t like the limitations of Twine or the strange syntax (non-syntax?) of Inform. Right now, though, I can’t recommend it for brand-new authors.

Versu

The last XYZZY finalist is Versu, an entirely new and radically different IF system. Unfortunately, at the time of writing it’s on permanent hiatus. Linden Labs (home of Second Life) hold the rights but have ceased all development, and creators Emily Short and Richard Evans have left for pastures new. I luckily downloaded Versu and a couple of stories to my iPad before it was cancelled, so I can at least review it from a player’s point of view. But it’s a real gut-punch that we’ll never get to try out the authoring tools, or see them stretched to their limit in ambitious games like Short’s lost epic Blood and Laurels.

I missed the brief opportunity to buy Blood and Laurels, so instead I’ll try one of the longer introductory games, The House on the Cliff. The game’s own blurb gives an excellent overview of what Versu aims to do (emphasis mine):

An accident to a carriage and mail coach strand a group of strangers in a desolate

stretch of coastland. The only source of shelter is an ancient, rambling estate,

where neither servants not master appear to be at home…Pick any character from a wide selection. Then play through the story forming

alliances or finding enemies among the other travelers; work to recover from the

crash, uncover the secrets of the estate, and perhaps pursue aims unique to your

own character.

Okay, so it’s a mystery story, set in perhaps the 19th or late 18th century; that’s not important here. What’s important is the form: you can play the same story in different roles, and explore how the different characters interact. It’s an attempt to marry traditional IF story mechanics with Sims-style simulation of human interactions.

If it works, that definitely meets both of the criteria I listed at the start. Getting this stuff right is hard, so if Versu (or some future successor) makes it significantly easier that’s a significant accomplishment. And if characters can be freely mixed and matched, it’s inherently combinatorial, so the potential for emergent gameplay is strong.

On starting the game, I am indeed presented with a configurable cast of characters (although I can only Randomize the whole cast, not hand-pick every member):

The main story interface generates text resembling a play, with lines by the various characters interspersed with descriptive snippets:

The doctor (to Elizabeth): It might be a bit forward of me, but under the

circumstances, allow me to introduce myself…The doctor: I have been seeing to a patient, when the fever broke, I thought it

might be safe to return to my own home.Elizabeth responds with obvious admiration.

Elizabeth (to the doctor): it’s all one to me, so long as there’s no contagion

to spread to the rest of us.

Oddly, the arrival of a new character is signalled by a simple canned line (“Elizabeth has fine eyes and a dancing wit”, “Mr Collins is a clergyman”) rather than a proper theatrical entrance, but I imagine that’s just a limitation of this particular story and not integral to Versu itself.

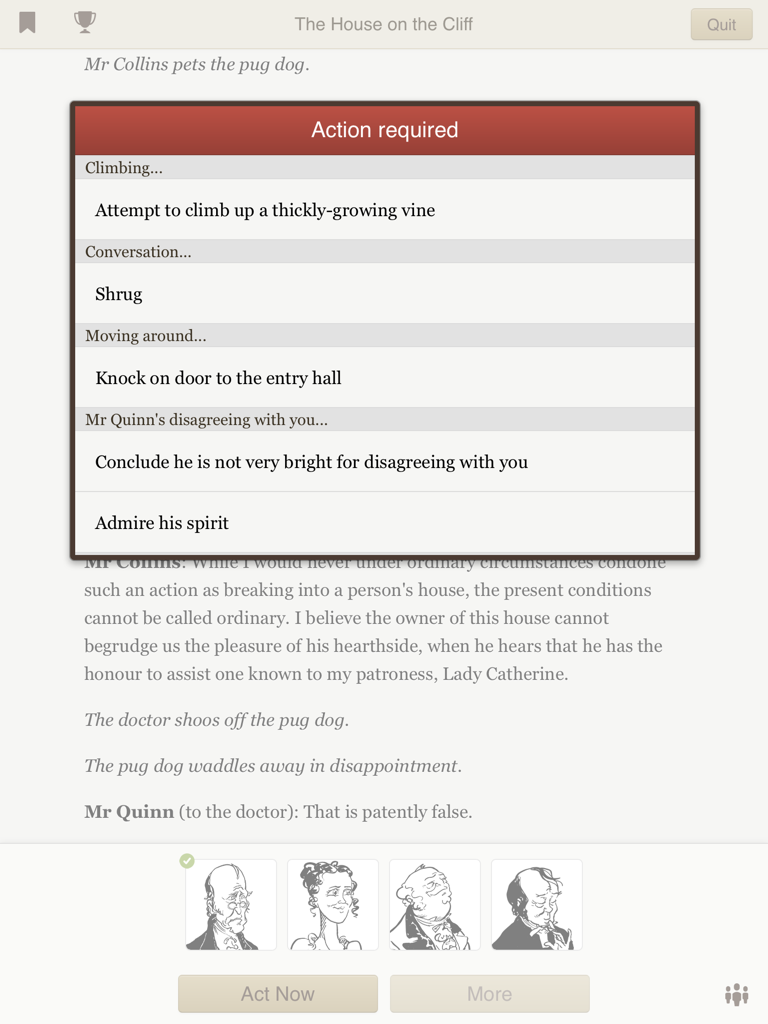

The player’s character (in this case, the doctor) isn’t given any special treatment; they have no more or less agency than the NPCs. You control your character via “Act Now” and “More” buttons—respectively, do something or wait to see if somebody else does something. Sometimes only one button is available: if “Act Now”, it becomes a multiple-choice game, if “More” you just have to keep tapping the button to advance the story. I find this a slightly awkward approach, as multiple taps are required for a single action; although when both buttons are available it oddly brings home the fact that you’re on a level playing field with the other characters, who are presumably in some fashion also tapping “More” and “Act Now” in the background as you play.

The “Act Now” button brings up a menu, usually with a long and bewildering mix of plot-advancing and social options. It’s instantly clear that this is a simulation, with a huge number of possible combinations, rather than a hand-written conversation tree that you could potentially strip-mine for content. Unfortunately the gears of the mechanism are often visible: for example, I was given the option to “Point out that Elizabeth has not yet spoken” immediately after she had said something (though not a direct response to the topic at hand). This tells me that making the text flow naturally remains hard; Versu doesn’t magically solve that problem.

Overall, I think the user interface could use a lot of work. The granularity of interaction feels way off: you’re given many chances to act, but acting takes several taps and there are a huge number of options, so the story proceeds very slowly. I’m sure this is partly a feature of this specific story, and other stories could move in bigger steps. And perhaps as a player there’s a better “Versu mindset” to get into, where you stop agonising over that huge menu of options and just get into character and go with the flow. (User interface tweaks could help there too—maybe it could cut the menu down to three or four options, with an extra “something else” button to see more.)

UI aside, is it actually fun to play? So far I’m unconvinced. As I speculated above, “The House on the Cliff” does marry an interactive story to a social simulation, but the seams seem overly visible to me. When there are more than two characters on the stage, they talk at cross-purposes—there’s no strong through-line to the dialogue. And when interacting with another character, my options are generally story-based or social-sim-based, but rarely both. For example, after the line:

Mr Quinn (to the doctor): That is patently false.

I’m only given the option to “conclude that he is not very bright for disagreeing with you” or “admire his spirit,” and not to actually say something in response (which might reveal character and advance the plot).

So, how well does Versu fit my two criteria for Technological Development in practice? I’m of two minds here. It’s attacking a very hard problem, and even though it doesn’t entirely solve that problem, it would clearly be a great platform for other people to build on. The user interface could use an overhaul, but the generative possibilities are definitely there: with the right level of narrative granularity, I can definitely see how playing a Versu game might feel like being in an improv theatre troupe. But would that format be a rich trove of possibilities, or would it turn out to be a restrictive dead end? I don’t know. Real-life theatre is still going strong, and the dream of “Hamlet on the holodeck” has inspired IF theorists for decades. Versu gets closer to that dream than anything else I’ve seen.

If it were still in development, I’d say Versu is promising but not quite there yet. Unfortunately it looks like we’ll never get a chance to see what might have been, or even to play any games that really exercise its potential; but hopefully the ideas behind it will take root and emerge in some other form.

This was an interesting overview; thank you!

Thanks for your review of adv3Lite. I’m still kicking myself for those errors in the Quick Start Guide that still hadn’t come to light by version 1.1, but they’ll be corrected in the next version, and I’ll look into your suggestion of a flowchart to guide people to the best bit of documentation to start with (though I think I might implement it in some other form than a flow-chart).

Just a couple of responses to your parser woes. Perhaps this does need to be better documented somewhere, but to get your HANG ON variants to work the way you want you needed to do a bit more work, something like (this isn’t complete but it gives the general idea):

VerbRule(HangOn)

'hang' ('up'|) singleDobj 'on' singleIobj

: VerbProduction

action = HangOn

verbPhrase = 'hang/hanging (what) (on what)'

missingQ = 'what do you want to hang; what do you want to hang it on'

;

VerbRule(HangOnWhat)

[badness 50] 'hang' ('up'|) singleDobj

: VerbProduction

action = HangOn

verbPhrase = 'hang/hanging (what) (on what)'

missingQ = 'what do you want to hang; what do you want to hang it on'

missingRole = IndirectObject

iobjReply = onSingleNoun

;

You’d then find that both your “hang up cloak” and the disambiguation prompt to HANG CLOAK would work rather more smoothly. In particular you could then type HANG CLOAK and respond to the disambiguation prompt with either ON HOOK or just HOOK and it would work either way.

The reason you can’t do this with PUT CLOAK is that the parser can’t tell whether this is an incomplete PUT IN, PUT ON, PUT UNDER or PUT BEHIND command, so simply replying HOOK doesn’t give the parser enough information to go on. Here the parser needs the player to supply a preposition to tell it what action is being attempted.

But thanks again for an interesting review. I’ll now see what improvements I can make in the light of it!